Common Mistake #8: Buying Whole Life Insurance Instead of Term (Without Doing the Math)

Life insurance is meant to transfer risk, not to function as a catch-all financial solution. Yet many individuals purchase whole life insurance without fully analyzing its cost structure, long-term trade-offs, or whether it aligns with their actual needs. In many cases, the decision is made early, framed as prudent planning, and rarely revisited.

This article explains why buying whole life insurance without doing the math is a common financial mistake, how its structure differs fundamentally from term insurance, and why the long-term impact often looks very different from initial expectations.

Key takeaways

- Whole life insurance includes life insurance coverage and a savings component and typically carries higher premiums and fees.

- The structure is designed to emphasize contractual guarantees, which may result in less efficiency or flexibility compared to other options.

- Premium differences compound into large opportunity costs over time.

- Insurance needs and investment needs are not always the same.

- The right choice depends on purpose, not labels.

Why whole life insurance can seem like the responsible choice

Whole life insurance is often presented as comprehensive. It offers permanent coverage, fixed premiums, and a cash-value component that grows over time. To many buyers, this combination feels safer and more disciplined than a policy that expires.

The framing reinforces that perception. Whole life is often described as "guaranteed", "forced savings", or "something you won’t lose", while term insurance is framed as temporary or incomplete. For individuals thinking about dependents, long-term security, or legacy planning, permanence can feel reassuring.

At this stage, the decision appears conservative and future-oriented.

Where the structure changes the economics

A key distinction between whole life and term insurance relates to how premiums are allocated, rather than duration alone.

Whole life premiums are generally significantly higher because they fund multiple components at once: insurance coverage, administrative costs, commissions, reserves, and a cash - value account with conservative growth assumptions. Early premiums are heavily front-loaded toward costs rather than accumulation.

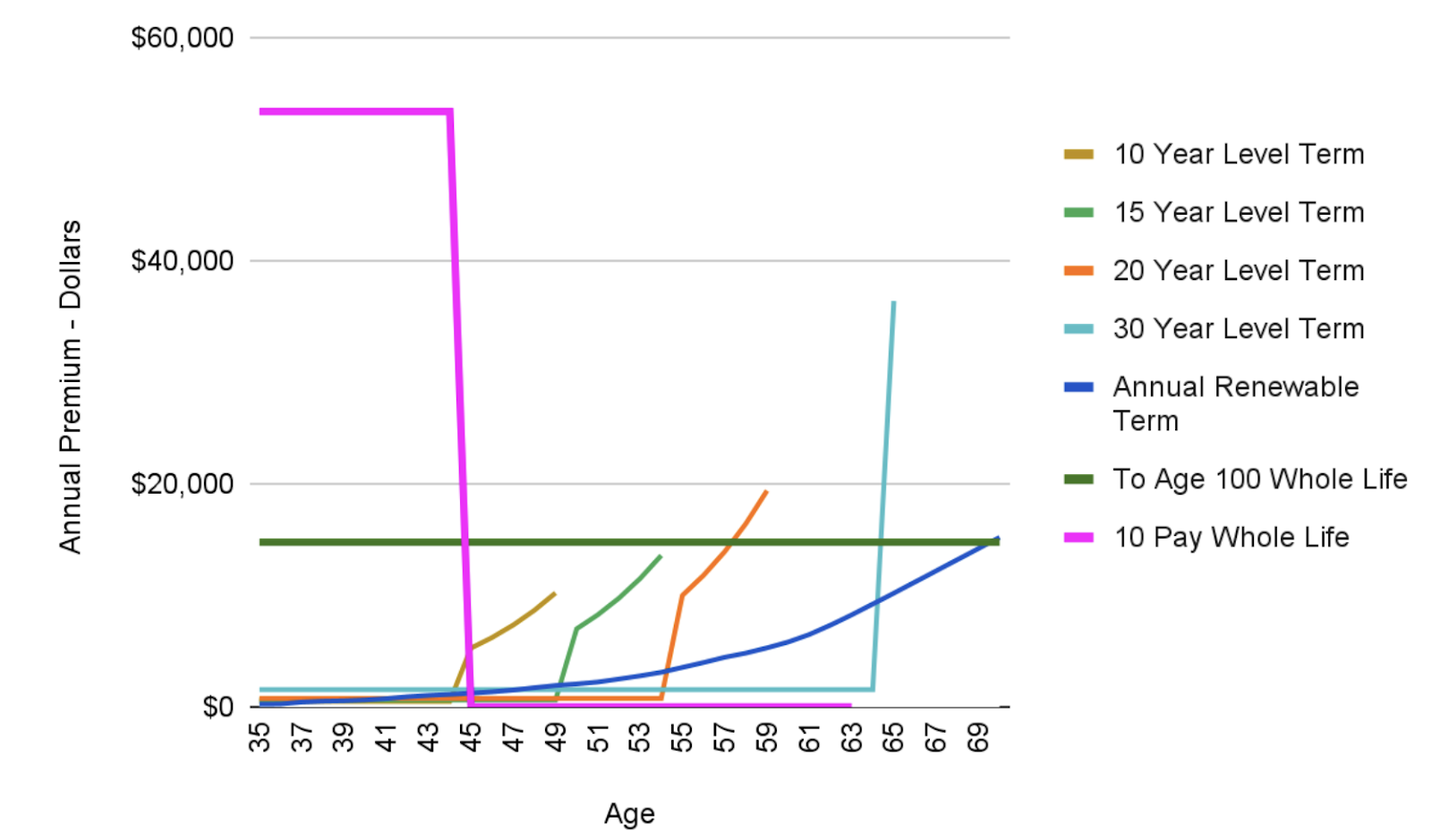

The chart highlights how this structural difference shows up immediately in annual premiums.

The gap is not incremental. For the same coverage amount, whole life policies require substantially higher upfront and ongoing commitments. That difference represents capital being directed toward contractual guarantees and policy mechanics rather than flexibility or alternative uses.

Term insurance, by contrast, is narrowly focused. Premiums primarily pay for pure risk coverage during a defined period, without attempting to serve as a savings vehicle.

This is where the logic breaks. Combining insurance and long-term saving into a single product does not eliminate trade-offs - it embeds them.

How the cost difference compounds over time

Because whole life premiums are substantially higher than term premiums for the same death benefit, the difference is not marginal - it is structural.

Over long horizons, the excess premium paid into whole life policies represents capital that could have been allocated elsewhere. Even if the policy’s cash value grows steadily, the internal rate of return often reflects the product’s conservative design and layered costs.

The consequence is not that the whole life "fails", but that it competes with alternative uses of capital under very different assumptions. When those assumptions are not examined, buyers may overestimate what the policy is accomplishing.

This gap often becomes clear only years later, when flexibility is limited and early costs are already sunk.

Why the trade-off is easy to overlook

Whole life insurance is typically purchased with long time horizons in mind. Because outcomes unfold slowly, early performance is rarely scrutinized. Policy illustrations project stability, not volatility, and cash value growth is incremental rather than dramatic.

There is also inertia. Once a policy is in force, changing course can feel complex, emotionally charged, or financially punitive. As a result, initial assumptions persist even as circumstances change.

The issue is not that whole life is opaque. It is its complexity that makes comparison less intuitive without deliberate analysis.

A clearer way to frame the decision

Investors who approach this decision more deliberately often start with a simple separation:

Insurance exists to transfer risk; investing exists to grow capital.

This framing does not rule out permanent insurance products. It clarifies their role. Coverage decisions are often evaluated based on the duration and magnitude of the underlying risk, while capital decisions are commonly assessed using factors such as cost, return potential, and flexibility.

When the two are blended, understanding what is being paid for - and what is being forgone - becomes essential.

The goal is not to optimize one product, but to align tools with purposes.

When whole life insurance may still be intentional

Whole life insurance is not inherently inappropriate. Some individuals value its contractual guarantees, estate planning characteristics, or predictability, particularly in specific tax or legacy contexts.

The distinction lies in analysis.

Buying whole life becomes a mistake when it is chosen by default, without comparing costs, assumptions, and alternatives. It can be intentional when the structure aligns with clearly defined goals and constraints.

The problem is not the product. It is skipping the math.

How optimized is your portfolio?

PortfolioPilot is used by over 40,000 individuals in the US & Canada to analyze their portfolios of over $30 billion1. Discover your portfolio score now:

.webp)