Common Mistake #21: Leaving Cash Idle in a Checking Account

Cash is a foundational part of any financial plan. It provides liquidity, flexibility, and short-term stability. Yet many investors hold substantially more cash in checking accounts than their immediate needs require. According to Federal Reserve data, US households and nonprofit organizations collectively held roughly $4.9 trillion in checkable deposits and currency - the core components of transaction accounts - as of mid-2025, representing sizable cash balances that typically earn little to no interest compared with other financial assets, even in periods when short-term interest rates are meaningfully positive.

This article explains why leaving excess cash idle in a checking account is a common but overlooked mistake, how it quietly weakens long-term financial outcomes, and why the cost tends to surface only after time has already reduced options.

Key takeaways

- Idle cash carries a real cost even when balances appear stable.

- Inflation and foregone interest steadily reduce purchasing power.

- The primary risk of excess cash is gradual erosion, not sudden loss.

- Liquidity does not require sacrificing productivity.

- Assigning cash a clear role improves financial efficiency.

Why holding extra cash feels sensible

Keeping cash in a checking account feels prudent. Funds are immediately accessible, balances do not fluctuate, and there is no visible risk of loss. For many investors, cash represents safety and optionality - resources that can be deployed at any moment.

This preference is reinforced during volatile markets. When asset prices move unpredictably, cash appears neutral: it neither rises nor falls. Checking accounts, in particular, offer simplicity and certainty, which can feel valuable when other parts of a portfolio are unsettled.

At this stage, holding extra cash appears conservative rather than costly.

Where the logic breaks

The issue is not liquidity. It is a misclassification.

Checking accounts are designed for transactions, not long-term storage. When cash intended for medium - or long-term use remains in an account earning little or no interest, its real value declines over time.

Even modest inflation steadily erodes purchasing power. Over long periods, inflation quietly reduces the real value of cash, even when nominal balances appear unchanged.

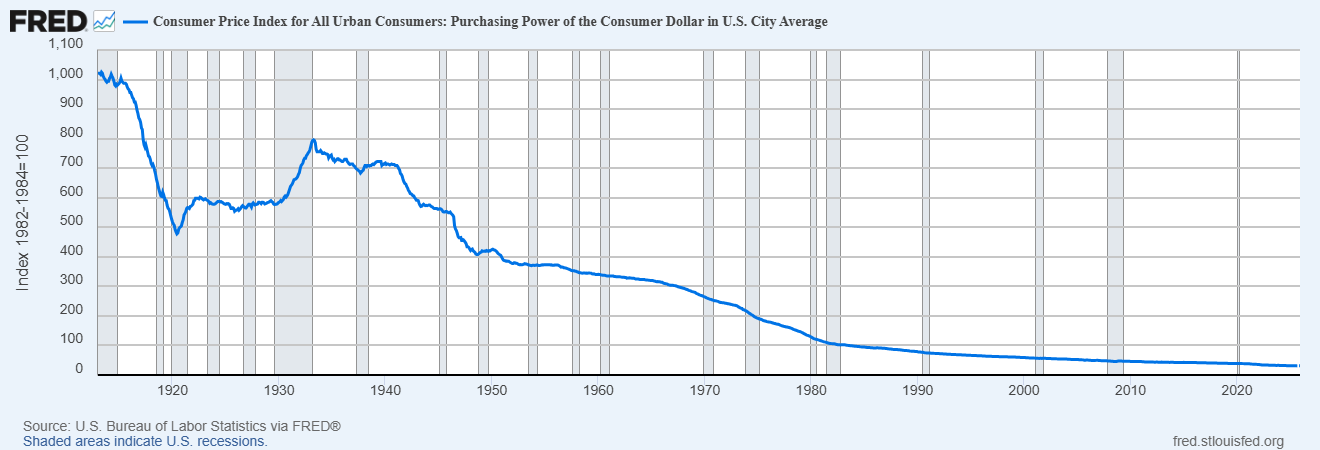

[Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics via Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED). This is an interactive chart. Readers can adjust time ranges, explore specific periods, and download the underlying data directly from the Federal Reserve’s public database. ]

The decline is gradual rather than dramatic, which is why it often goes unnoticed. But over decades, idle cash consistently loses purchasing power, turning apparent safety into structural erosion.

When short-term interest rates rise, the gap widens between what idle cash earns and what it could earn with minimal additional risk. The cash still feels safe, but economically, it is moving backward.

This is where the structural cost emerges: cash that appears risk-free is still exposed to inflation and to opportunity loss.

How idle cash becomes a long-term drag

Unlike investment losses, the cost of idle cash does not show up as a drawdown. Account balances remain unchanged. Statements look stable. There is no single moment that signals failure.

The effect unfolds gradually. Over the years, purchasing power has declined. Future goals require larger balances than originally planned. What once functioned as a comfortable buffer becomes less effective at supporting spending or flexibility.

This outcome is not driven by poor timing or bad decisions. It is the mechanical result of leaving capital unproductive for extended periods.

In this sense, idle cash behaves less like a neutral asset and more like a slowly depreciating one.

Why the cost is easy to miss

Cash does not trigger behavioral alarms. There is no volatility, no negative headlines, and no daily price movement. The absence of visible change creates the impression that nothing is happening.

But neutrality is not efficiency. In practice, excess cash often builds up gradually, as inflows outpace spending without a clear review process.

Some investors reduce this risk by separating day-to-day checking from longer-term balances, making accumulation more visible.

Simple balance thresholds or alerts can also help signal when cash has drifted beyond its intended role.

When excess cash accumulates without a defined purpose beyond immediate spending or emergency needs, it begins to crowd out other financial priorities. Over time, it can reduce real returns, limit participation in higher-yielding assets, and weaken long-term plans.

The problem is not holding cash. It is holding undifferentiated cash.

A more durable way to think about cash

Investors who manage cash more effectively tend to focus on the role rather than the location:

Cash is assigned a purpose, not just a place.

Transaction cash remains in checking accounts. Emergency reserves and near-term savings are held in vehicles that preserve liquidity while earning interest. Capital not needed in the near term is allocated according to broader goals and risk tolerance.

This approach does not reduce flexibility. It clarifies intent. Cash stays liquid, but it no longer remains idle by default.

The objective is not optimization. It is alignment.

When idle cash can still be intentional

There are situations where holding additional cash in a checking account is reasonable - such as covering upcoming expenses, managing irregular income, or maintaining simplicity during short transitions.

The distinction lies in intent and duration.

Leaving cash idle becomes a mistake when it persists beyond its purpose and substitutes for a clearer plan. Cash works best when it supports financial goals, not when it quietly delays them.

How optimized is your portfolio?

PortfolioPilot is used by over 40,000 individuals in the US & Canada to analyze their portfolios of over $30 billion1. Discover your portfolio score now:

.webp)