Common Mistake #29: Not Knowing the Fees in Your Retirement Accounts

Fees rarely feel urgent. They don't show up as losses, don't trigger alerts, and don't fluctuate with headlines. According to long-running analyses of industry fee trends, including research by the Investment Company Institute and fee studies from Morningstar, ongoing expense ratios - even when relatively low - directly reduce the net returns that investors capture over decades, because these costs are deducted each year and compound against long-term outcomes. Over time, small differences in expense ratios can add up to meaningful differences in accumulated wealth.

Many investors contribute diligently to their 401(k)s and IRAs without ever examining what they're paying to invest. This article explains why not knowing the fees inside retirement accounts is a common and costly mistake, how those costs quietly erode returns, and why the damage often goes unnoticed until it's too late to easily reverse.

Key takeaways

- Fees reduce returns every year, regardless of market performance.

- Small percentage differences compound into large dollar gaps over time.

- Retirement account fees are often opaque and easy to ignore.

- The cost shows up as opportunity lost, not money withdrawn.

- Awareness matters more than precision.

Why fees rarely feel like a problem

Many retirement accounts don't make fees obvious. They're embedded in fund expense ratios, administrative charges, or plan-level costs. There's no monthly bill. No transaction labeled "fees paid".

Account balances may still rise, reinforcing the sense that nothing is wrong. Contributions continue. The statements look healthy.

Up to this point, nothing feels broken.

That's exactly why fees are so easy to overlook.

Here's the part most investors don't fully internalize

Fees don't just reduce returns. They compound against you.

A 0.75% annual fee doesn't sound dramatic. But over 30 or 40 years, that cost applies not only to contributions, but to every dollar of growth those contributions could have generated.

So what? Two investors with identical contributions and identical markets can end up with meaningfully different outcomes - solely because of costs.

This is where "minor" turns structural.

This is where fees quietly do the most damage

Hypothetical example: Imagine two employees contributing the same amount to their retirement plans over decades. One invests in options with higher embedded fees. The other invests in lower-cost alternatives available within the same plan.

Neither investor changes behavior. Neither makes a mistake. Markets perform identically for both.

Over time, the higher-fee account grows more slowly. The difference isn't dramatic in any single year. But at retirement, the cumulative gap is large - created entirely by friction.

Nothing was taken out. Less was simply allowed to grow.

Why retirement account fees are hard to see

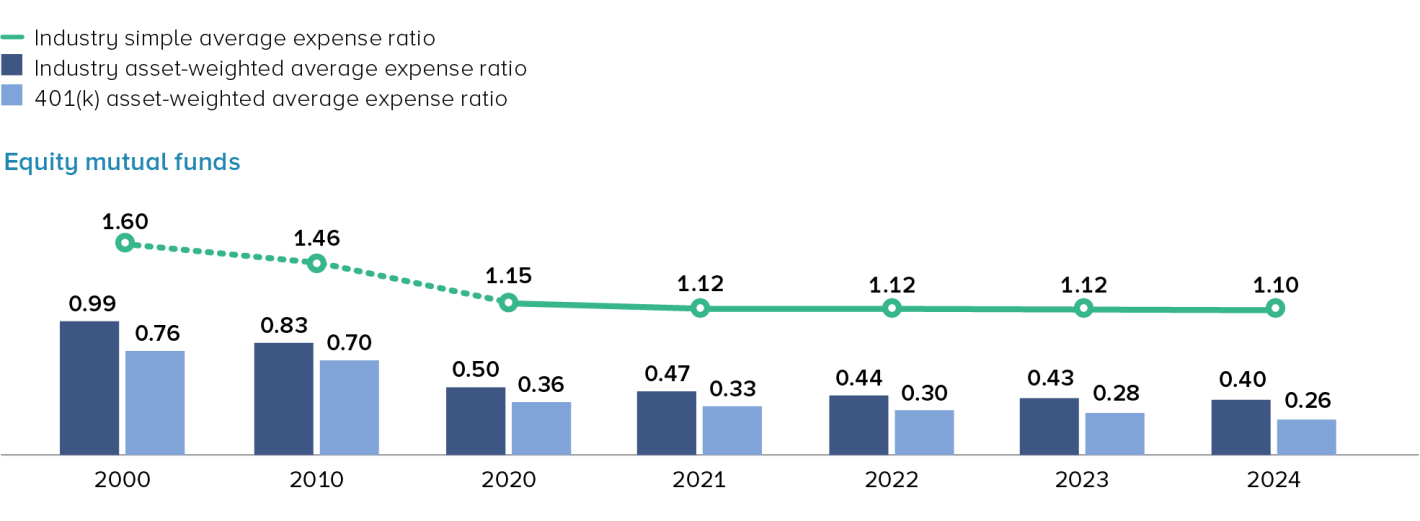

Over time, average fund fees have declined, especially as low-cost index products gained market share. This trend can create the impression that fees no longer matter. In reality, lower fees do not eliminate fee drag - they simply reduce it.

What this chart doesn’t show is the cumulative impact of these fees over decades. Even at today’s lower levels, expense ratios quietly reduce the base on which returns compound - year after year.

Several factors obscure fee awareness:

- Expense ratios are quoted in percentages, not dollars

- Administrative costs may be layered and indirect

- Statements emphasize balances, not drag

- Plan menus vary widely in transparency

Many investors also assume fees are "the price of access" or that choices are limited. In employer-sponsored plans, inertia and default selections often do the rest.

The issue isn't that fees are hidden. It's that they're quiet. In practice, retirement account costs often come from multiple layers. Common sources include fund expense ratios, plan-level administrative fees, recordkeeping charges, and, in some cases, revenue-sharing arrangements embedded within investment options. Individually, these fees may appear modest, but together they determine how much return is allowed to compound over time.

Why does this mistake persist even among savers

Fee awareness requires context. A 0.5% difference feels abstract without understanding compounding. And because fees don't create visible pain, they rarely trigger action.

Behavioral research shows that investors tend to focus disproportionately on salient outcomes - such as short-term volatility, headline losses, and dramatic market moves - while paying less attention to slow, persistent drags like fees, tax inefficiencies, and opportunity costs, reflecting well-documented cognitive biases in decision-making.

Fees exploit that blind spot perfectly.

The danger isn't overpaying once. It's doing so for decades without noticing.

The one reframe that changes the conversation

Investors who address this mistake often adopt a simple reframe:

Fees are a permanent headwind, not a one-time cost.

This perspective shifts attention from short-term performance to long-term efficiency.

Supporting actions - such as reviewing expense ratios within available plan options or understanding how total costs affect long-horizon growth - exist to reinforce awareness, not to force specific choices.

The goal isn't chasing the cheapest option. It's avoiding unnecessary drag.

When higher fees may still exist

Not all higher fees are automatically unjustified. Some plans have limited menus. Some strategies involve additional services or complexity. In employer-sponsored accounts, choices may be constrained.

The distinction, as with other mistakes in this series, is knowledge.

Fees become a mistake when they are unknown and unexamined - not when they are understood and accepted within a broader plan.

Awareness doesn't guarantee perfection. It prevents complacency.

How optimized is your portfolio?

PortfolioPilot is used by over 40,000 individuals in the US & Canada to analyze their portfolios of over $30 billion1. Discover your portfolio score now:

.webp)