Common Mistake #2: Ignoring Asset Allocation (And Calling It "Diversified")

Many investors believe they are diversified because they own multiple funds, accounts, or securities. Yet decades of market research suggest diversification is driven far more by asset allocation than by the number of holdings. According to studies frequently cited by Vanguard, more than 90% of a portfolio's long-term return variability is explained by how assets are allocated across categories like stocks, bonds, and cash - not by individual security selection.

Despite this, asset allocation is often treated as secondary. Portfolios become collections of investments rather than intentionally structured systems. This article explains why ignoring asset allocation is one of the most common - and quietly damaging - investor mistakes, and why it often goes unnoticed until stress exposes it.

Key takeaways

- Diversification depends on asset mix, not how many holdings appear in a portfolio.

- Many portfolios that look balanced behave like a single concentrated bet.

- Correlation, not variety, determines whether diversification works during stress.

- Asset allocation mistakes usually reveal themselves late - when changing course is hardest.

- A portfolio can seem diversified while carrying far more risk than intended.

Why "Looking diversified" is so convincing

At a glance, many portfolios appear well constructed. They include multiple funds, span domestic and international markets, and sit across different accounts. This variety creates comfort.

The issue is that visual complexity often substitutes for true diversification.

Holdings are frequently added incrementally - a new ETF here, a different strategy there - without revisiting the portfolio as a whole. Over time, exposure drifts. Risk concentrates. Yet nothing feels reckless, because no single decision appears extreme.

Up to this point, nothing looks wrong.

That's why this mistake persists.

Here's the problem most investors miss

Diversification is not about how investments are labeled. It's about how they behave together.

Asset allocation determines how a portfolio responds to growth slowdowns, interest rate changes, inflation shocks, and liquidity stress. Research dating back to Brinson, Hood, and Beebower shows that allocation explains the majority of portfolio behavior over long periods - including volatility, drawdowns, and recovery paths.

Security selection can influence outcomes at the margins. Allocation defines the experience.

So what? A portfolio dominated by a single asset class may perform well for years - until market conditions change and correlations rise.

This is where diversification quietly breaks

The weakness in superficial diversification rarely shows up during calm markets. It emerges during stress.

Hypothetical example: Imagine an investor holding eight different equity funds across multiple accounts. Some emphasize growth, others value, some US, others global. On paper, the portfolio looks varied. In practice, over 85% of its risk still comes from equities.

When markets fall sharply, nearly every holding declines together.

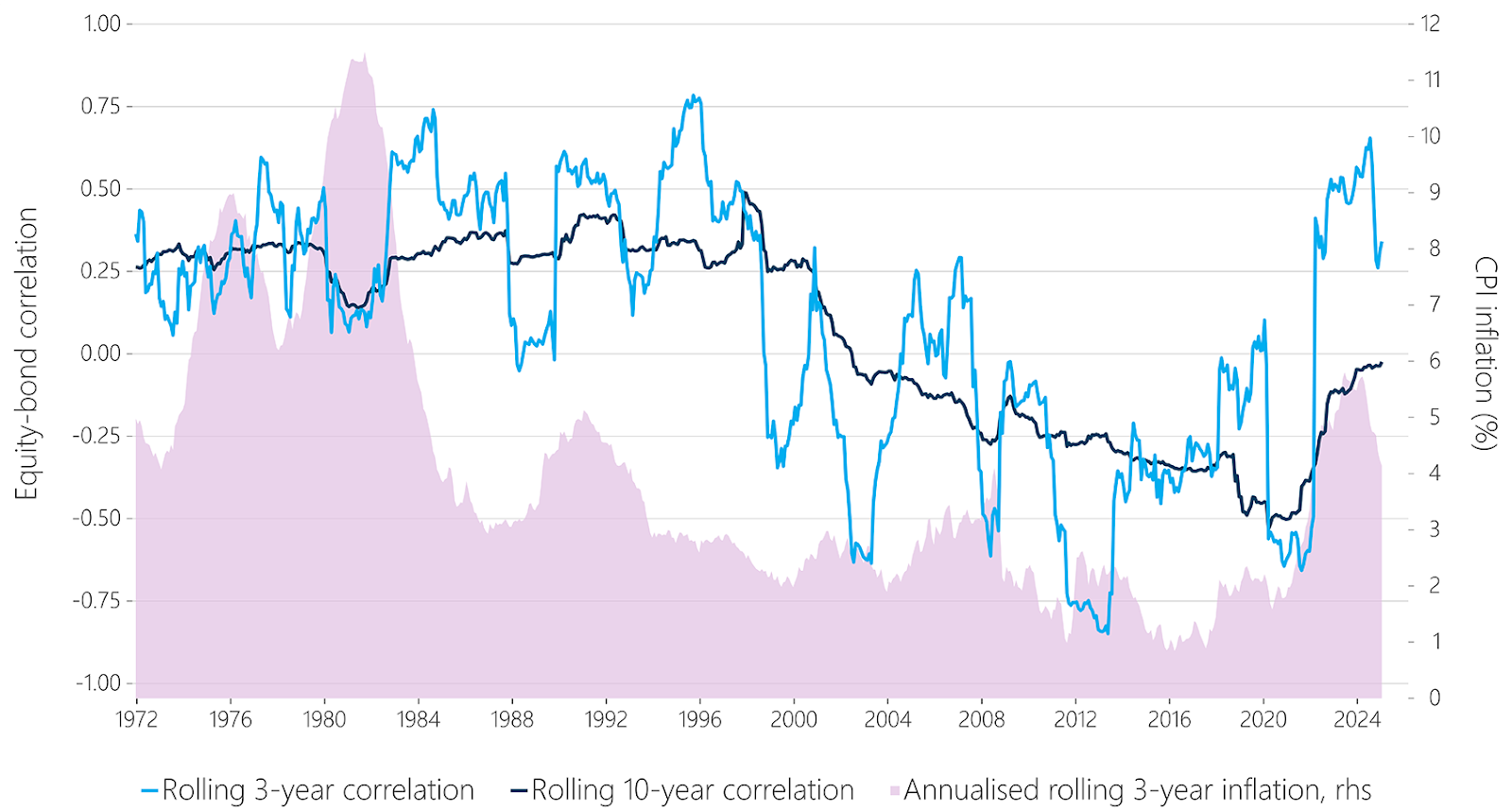

This pattern is not anecdotal. Historical data show that correlations between major asset classes are not stable and tend to rise during periods of market stress - precisely when diversification is expected to provide protection.

Rolling equity-bond correlations over time show that relationships between asset classes shift meaningfully across market regimes. During stressed periods, correlations often rise or turn positive, reducing the diversification benefits investors expect from holding multiple assets.

Nothing is wrong with any individual fund. The failure is collective. Assets that once appeared distinct begin moving in sync, exposing a level of concentration the investor never intended.

This is why diversification errors feel invisible - until they matter most.

Why the consequences arrive so late

Ignoring asset allocation often carries no immediate penalty. During strong markets, concentrated exposure can even feel like conviction. Returns reinforce confidence, and the absence of friction delays reconsideration.

The cost appears during downturns.

Portfolios with hidden concentration tend to experience:

- Larger drawdowns

- Longer recovery periods

- Higher emotional stress

- Greater temptation to exit at the wrong time

Morningstar research has consistently shown that investor underperformance is driven less by product choice and more by behavior during volatility. Poor asset allocation amplifies that stress, making disciplined decisions harder to sustain.

The mistake isn't a lack of knowledge. It's delayed feedback.

Why asset allocation is so easy to downplay

Asset allocation doesn't feel actionable. It doesn't produce short-term wins or narratives of skill. It lacks the emotional reward of picking the "right" investment.

As a result, many investors focus on selection and timing - decisions that feel active - while neglecting the quieter structure underneath.

Daily market commentary and short-term performance narratives can reinforce this tendency, encouraging frequent adjustments rather than long-term structure.

Over time, reacting to headlines or individual sound bites can unintentionally increase concentration risk, even when each change feels small in isolation.

There is also a subtle illusion of control. Owning many investments feels safer than committing to a defined allocation. But safety built on ambiguity is fragile. When volatility rises, uncertainty compounds fear.

This is why allocation decisions feel abstract in good times - and painfully concrete in bad ones.

The one constraint that reduces hidden risk

Investors who avoid this mistake often adopt a simple governing principle:

Asset allocation is defined first. Investments are chosen second.

This doesn't prevent losses or volatility. It clarifies intent.

Supporting practices - such as reviewing exposure across accounts or monitoring allocation drift - exist to enforce this constraint, not replace it. The goal is not precision. It's resilience.

When concentration is intentional - and when it isn't

Concentration is not inherently wrong. Some investors knowingly accept higher risk in pursuit of higher potential returns, particularly with long time horizons.

The distinction is awareness.

Concentration supports a strategy when it is deliberate, understood, and aligned with risk tolerance. It becomes a mistake when it emerges unintentionally - through accumulation, inertia, or assumptions.

Asset allocation works when it reflects intention. It fails when it reflects neglect.

How optimized is your portfolio?

PortfolioPilot is used by over 40,000 individuals in the US & Canada to analyze their portfolios of over $30 billion1. Discover your portfolio score now: