Common Mistake #8: Overconcentrating on Home Equity as an "Investment"

For many households, a home is the largest asset on the balance sheet. Over time, rising property values can make home equity feel like both shelter and strategy. According to data from the Federal Reserve's Survey of Consumer Finances, primary residences account for a significant share of net worth for middle - and upper-middle-income households in the US.

That prominence often leads to a quiet assumption: the house is the investment. This article explains why overconcentrating on home equity as an investment is a common but underexamined mistake, how it creates hidden liquidity and growth risks, and why it often feels sensible right up until flexibility is needed.

Key takeaways

- Home equity is concentrated, illiquid, and location-dependent.

- Price appreciation does not equal investable returns.

- Relying on housing wealth can limit diversification and flexibility.

- Home equity risk often surfaces during economic stress or life changes.

- A home can support a financial plan without carrying it.

Why home equity feels like a safe bet

Homeownership carries emotional and financial validation. Mortgage payments build equity. Prices tend to rise over long periods. Headlines often frame housing as a reliable store of wealth.

There's also lived experience. Owners see neighbors sell at higher prices. Statements show growing equity. The progress feels tangible.

Up to this point, nothing looks risky. In fact, it looks prudent.

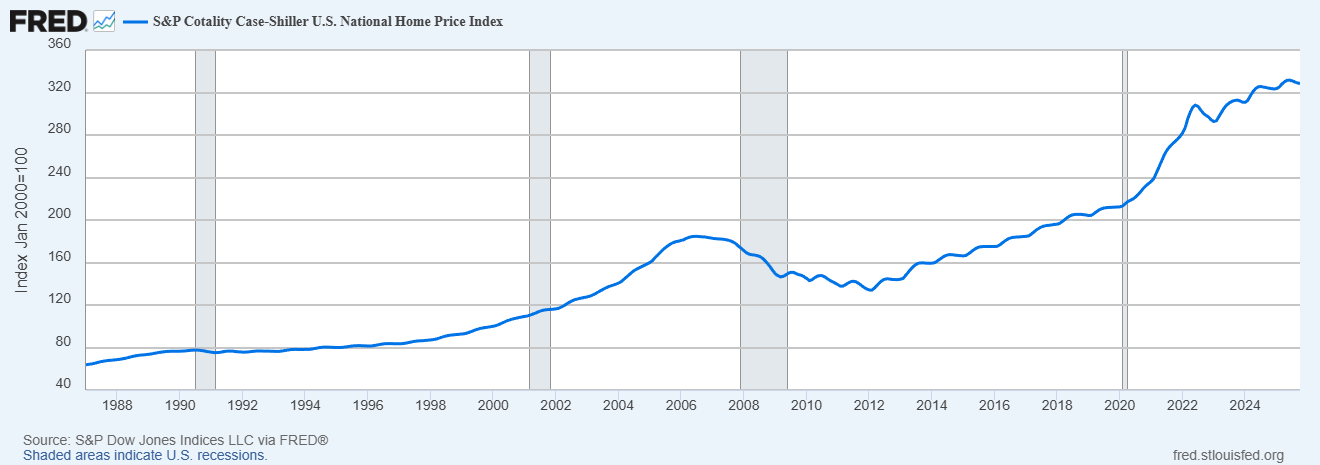

Long-term home price data helps explain this perception. US home prices have historically trended upward, reinforcing the idea that housing is a stable and reliable store of value.

This steady appreciation is precisely what makes home equity feel like an investment. But price growth alone does not determine whether an asset is diversified, liquid, or flexible when conditions change.

That's why many investors come to treat home equity not just as housing wealth, but as their primary investment engine.

Here's the assumption that quietly changes the risk profile

Home equity is often treated as interchangeable with portfolio assets. But structurally, it behaves very differently. Unlike diversified investments, home equity is:

- Tied to a single location and market

- Difficult to access without selling or borrowing

- Exposed to local economic conditions

- Costly to transact against

So what? Appreciation on paper does not automatically translate into usable capital.

This is where the investment narrative begins to break down.

This is where concentration and illiquidity collide

Hypothetical example: Imagine a homeowner whose net worth is largely tied up in a primary residence. Property values have risen steadily for years. Equity builds. Confidence grows.

Then circumstances change. A job relocation, a health expense, or a market slowdown creates a need for liquidity. Selling isn't immediate. Borrowing depends on rates and credit conditions. The equity exists - but access is limited.

At the same time, housing markets can stagnate or decline regionally, even when national averages look stable.

This is where home equity concentration becomes a constraint, not a cushion.

Why is housing appreciation often overstated as "Return"

Housing returns are frequently discussed in nominal terms, without accounting for:

- Property taxes

- Maintenance and repairs

- Insurance

- Transaction costs

- Inflation

Once these factors are considered, the real, investable return of a primary residence often looks more modest than headline price appreciation suggests.

That doesn't mean homeownership is a poor financial decision. It means it serves a different role.

A home provides utility and stability. It does not function like a liquid, diversified investment portfolio.

Why is this risk easy to miss

Home equity grows quietly. There's no daily price ticker. No volatility dashboard. That stability feels reassuring.

At the same time, rising equity can reduce urgency to save or invest elsewhere. Contributions slow. Portfolios lag. Over time, housing wealth crowds out financial diversification.

The danger isn't owning a home. It's letting one asset dominate the entire financial picture.

The one reframe that restores balance

Investors who avoid this mistake often adopt a simple reframe:

A primary residence is a foundation, not a portfolio.

This reframing clarifies roles. Housing provides shelter and long-term stability. Investments provide liquidity, diversification, and flexibility.

Supporting practices - such as tracking net worth by asset type or evaluating how much future spending depends on housing wealth - exist to reinforce this clarity, not diminish the value of homeownership.

The goal isn't to downplay housing. It's to right-size it.

When home equity can play a larger role

For some investors, housing naturally represents a larger share of net worth - especially early in life or in high-cost markets. That alone isn't a mistake.

The distinction, again, is intent.

Home equity concentration becomes risky when it substitutes for diversified saving and investing, rather than complementing them.

A home works best when it supports financial security, not when it bears the entire burden.

How optimized is your portfolio?

PortfolioPilot is used by over 40,000 individuals in the US & Canada to analyze their portfolios of over $30 billion1. Discover your portfolio score now: