Common Mistake #3: Panic-Selling During Market Downturns

Market downturns feel urgent in a way few other financial events do. Some of the strongest market rebound days over the last several decades have occurred during or immediately after periods of extreme volatility - often when investor sentiment was at its worst. Yet investor behavior data consistently show that many people reduce exposure precisely during those moments.

This gap between market behavior and investor behavior is not driven by a lack of information. It's driven by panic. This article explains why panic-selling during downturns is one of the most persistent investor mistakes, how it quietly converts temporary declines into permanent losses, and why it continues to feel rational even when the long-term cost is high.

Key takeaways

- Panic-selling turns temporary market declines into realized losses.

- The largest recovery days often occur when fear is still widespread.

- Emotional relief from selling is immediate; financial damage is delayed.

- Most underperformance stems from exit and re-entry timing, not asset choice.

- Preventing panic-selling is more about rules than resolve.

Why selling during a drop feels responsible

When markets fall sharply, selling feels like action. Losses mount, headlines worsen, and uncertainty spikes. Reducing exposure appears prudent, especially when framed as "risk management."

This instinct is reinforced by short-term relief. Selling stops the bleeding. Account balances stabilize. Stress eases.

Continuous exposure to real-time market commentary during periods of sharp declines can intensify this instinct, making short-term action feel urgent and necessary.

Stepping back from the constant news flow during volatile periods can help investors avoid decisions driven more by emotional pressure than by long-term plan alignment.

Up to this point, the decision feels controlled, even disciplined.

That's why panic-selling is so common. It doesn't feel like panic in the moment. It feels like caution.

Here's the part most investors don't see in real time

The real damage from panic-selling rarely comes from selling itself. It comes from what happens next.

Market recoveries are uneven. Gains do not arrive gradually or politely. According to historical market return analyses, a disproportionate share of long-term equity returns comes from a relatively small number of powerful rebound days, many of which occurred during or immediately after periods of high volatility and market stress. Research on investor behavior consistently shows that many people reduce their exposure during those moments, increasing the risk of missing the very days that drive the bulk of long-term gains.

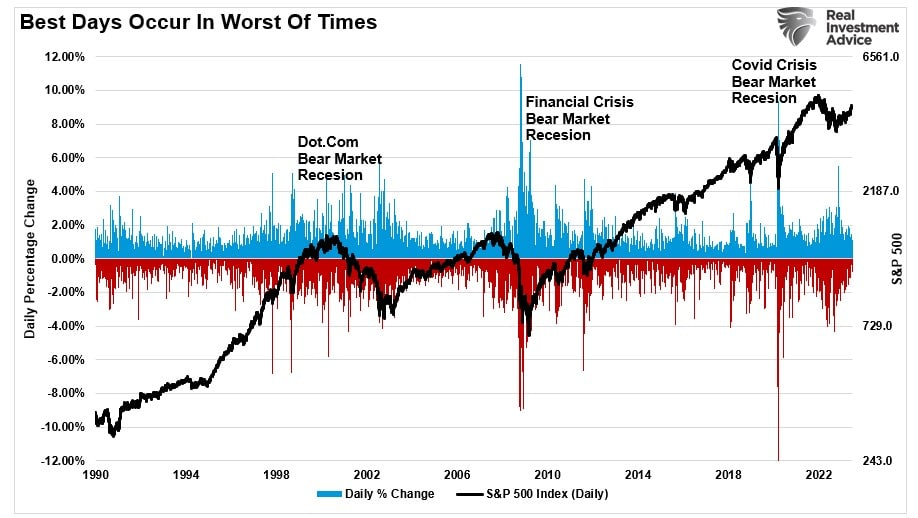

This pattern is visible in historical market data. Some of the strongest single-day gains in equity markets occurred during periods of extreme stress - often in the middle of bear markets or immediately after sharp declines.

Daily S&P 500 returns show that many of the strongest positive days occurred during major market crises, including the dot-com bust, the global financial crisis, and the COVID-19 sell-off. These rebound days often arrived while volatility and fear remained elevated.

This is why panic-selling is so costly. Investors who exit during periods of fear risk missing the very days that drive long-term recovery - turning what could have been temporary declines into permanent opportunity costs.

Those days often happen:

- Before economic data improves

- Before headlines turn positive

- Before investors feel confident re-entering

So what? Selling during fear removes exposure precisely when recovery risk is highest.

This is where panic-selling quietly breaks long-term plans.

This is where temporary losses become permanent

Hypothetical Example: Imagine an investor who sells after a 20% market decline to avoid further damage. The decision reduces stress and makes one feel protective. The investor waits for "confirmation" that conditions have stabilized.

Over the next few weeks, markets rebound sharply. Several of the best trading days occur amid continued volatility and negative news. By the time confidence returns, prices are meaningfully higher.

The loss is no longer temporary.

Nothing dramatic happened. No single decision was irrational. But the sequence transformed volatility into a permanent opportunity cost.

This is why panic-selling underperforms even when the initial instinct feels reasonable.

Why recovery days are so easy to miss

Market bottoms are rarely obvious. They form amid bad news, weak sentiment, and lingering fear. Confidence typically returns after prices rise, not before.

Behavioral research helps explain this pattern. Fear narrows focus. During stress, investors prioritize avoiding further loss over participating in uncertain gains. This asymmetry makes re-entry psychologically harder than exit.

Morningstar's investor return studies repeatedly show that self-directed investors tend to underperform the funds they own, not because of fees or fund quality, but largely because poorly timed exits and delayed re-entries widen the gap between what the funds generate and what investors actually capture.

The problem isn't analysis. It's timing under stress.

Why panic-selling persists across cycles

Many investors believe panic-selling is a mistake; others are less disciplined, less experienced, and less prepared.

But long-running behavior studies, including DALBAR's Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behavior, show that the gap between market returns and investor returns persists across decades and market environments.

The reason is simple: no one knows in advance which days matter most.

Avoiding many bad days does not offset missing a few critical good ones. Once that asymmetry is understood, panic-selling looks less like risk control and more like risk concentration.

The one rule that actually reduces panic risk

Avoiding panic-selling is less about emotional strength and more about removing discretion during stress.

Many investors adopt a single governing rule:

Long-term capital is not reduced based on market declines alone.

This doesn't prevent volatility or losses. It prevents irreversible decisions made under peak fear.

Supporting practices-such as a mandatory pause before selling, predefined rebalancing thresholds, or separating near-term cash from long-term assets-exist to enforce this rule, not replace judgment entirely.

The goal isn't bravery. It's a constraint.

When selling during a downturn can make sense

Selling during a market decline is not always a mistake. Some investors reduce exposure to meet liquidity needs, fund near-term expenses, or rebalance portfolios back to target allocations.

The distinction is intent.

Selling supports a plan when it serves a defined purpose. It becomes destructive when it is driven by fear and paired with uncertainty about re-entry.

Panic-selling fails not because selling is wrong, but because fear-driven exits rarely come with disciplined returns.

How optimized is your portfolio?

PortfolioPilot is used by over 40,000 individuals in the US & Canada to analyze their portfolios of over $30 billion1. Discover your portfolio score now: