Common Mistake #32: Ignoring Inflation in Savings and Retirement Goals

.webp)

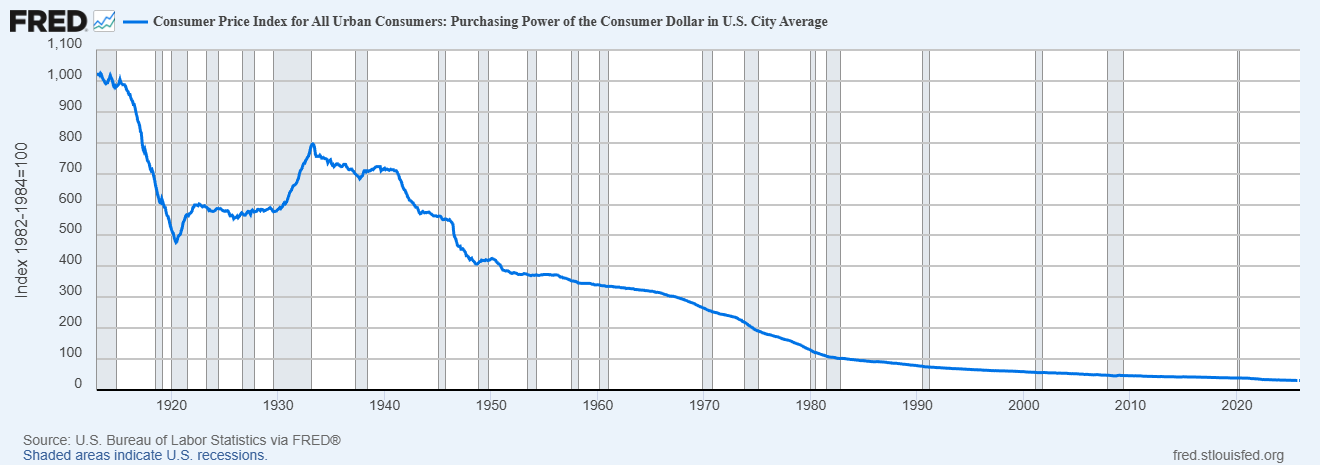

Inflation rarely feels urgent-until it is. According to long-term data from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, the US inflation rate has averaged roughly 3% per year over extended historical periods, meaning prices have tended to rise at that pace on average over much of the past century. That pace may sound modest, but over decades it quietly reshapes what money can actually buy. Yet many investors still set savings and retirement goals in nominal dollars, treating today's purchasing power as if it will still apply years from now.

This article explains why ignoring inflation is one of the most persistent planning mistakes, how it erodes progress invisibly, and why it often goes unnoticed until goals suddenly feel out of reach.

Key takeaways

- Inflation reduces purchasing power even when account balances grow.

- Long-term goals set in today's dollars can be misleading.

- The real risk is not inflation spikes-it's compounding erosion over time.

- Conservative-looking plans may be riskier than they appear.

- Accounting for inflation changes how progress should be measured.

Why is inflation easy to ignore when planning

Inflation doesn't arrive as a single event. It shows up gradually-higher grocery bills, rising rents, and increasing healthcare costs. Individually, these changes feel manageable.

When investors plan for the future, it's natural to think in today's terms. A retirement target of $1 million sounds substantial. A six-figure savings balance feels secure. These numbers anchor expectations.

Up to this point, nothing seems unrealistic.

That's why inflation is so often overlooked. It doesn't threaten balances-it threatens buying power.

Here's the assumption that quietly breaks long-term plans

Most savings goals are framed in nominal dollars. Inflation operates in real terms.

That gap matters.

At a 3% inflation rate, purchasing power is cut roughly in half over 24 years. This erosion is not theoretical. It can be observed directly in how much a dollar actually buys over time.

Over time, inflation steadily erodes purchasing power. Even modest inflation compounds meaningfully across decades, reducing what fixed nominal amounts can buy.

What feels like a generous income or savings target today may cover far less in the future. This doesn't require high inflation-just time.

So what? A plan can succeed on paper while failing in practice.

Ignoring inflation doesn't stop progress. It distorts measurement.

This is where "playing it safe" becomes risky

Hypothetical example: Imagine an investor targeting retirement with a large cash balance or ultra-conservative portfolio because it "preserves capital." Over time, the account balance remains stable and even grows slightly.

Meanwhile, inflation steadily erodes purchasing power.

By retirement, the balance looks intact - but the lifestyle it can support is meaningfully smaller than expected. The shortfall wasn't caused by market losses. It was caused by inflation outpacing growth.

This is where caution quietly turns into risk.

Why does inflation damage often show up late

Inflation's impact compounds silently. Early on, the difference between nominal growth and real growth feels small. Over longer horizons, it becomes decisive.

The problem is feedback timing.

Unlike market losses, inflation doesn't trigger alarms. Statements still go up. Balances still grow. The damage only becomes obvious when withdrawals begin-or when goals suddenly need to be revised upward.

By then, time is no longer an ally.

This is why inflation risk is most dangerous when it feels least urgent.

Why investors still underestimate inflation risk

Inflation is abstract. Market volatility is emotional. As a result, investors tend to focus on what feels threatening-short-term losses - while overlooking what feels gradual.

There is also a mental shortcut at play. Many investors assume inflation is someone else's problem: policymakers, wage growth, and future adjustments.

But inflation doesn't require bad decisions to cause harm. It works automatically.

Planning without inflation is not optimistic. It's incomplete.

The one shift that changes how progress is measured

Investors who avoid this mistake often adopt a simple reframing:

Long-term goals are evaluated in real purchasing power, not nominal dollars.

This doesn't require predicting inflation. It requires acknowledging it.

Supporting practices-such as stress-testing goals against different inflation assumptions or reviewing whether long-term growth has exceeded inflation over time - exist to reinforce this perspective, not complicate it.

The goal isn't precision. It's realism.

When inflation matters less - and when it matters most

Inflation matters most for long-term, fixed goals: retirement income, future living expenses, and healthcare costs.

It matters less for short-term savings intended for near-term use, where purchasing power erosion has less time to compound.

The distinction is horizon.

Inflation becomes dangerous when long-term goals are treated like short-term ones.

How optimized is your portfolio?

PortfolioPilot is used by over 40,000 individuals in the US & Canada to analyze their portfolios of over $30 billion1. Discover your portfolio score now: